AI offers potential transformational change on the scale of the Industrial Revolution. It may well deliver but it is equally reasonable to ask: what if it doesn’t? Or, even if it does, what if that success is already priced into today’s lofty share prices? Your investment portfolio is more exposed than you realise and many of the traditional places you could have sought shelter are now also hitched to the AI-bandwagon.

One area that stands out as offering genuine diversification potential is Value equities but, importantly, only if done properly. And, by properly, this means actively. Most passive value equity benchmarks are stuffed full of the same technology names that you’re seeking to diversify away from. If your aim is to “AI-proof” your portfolio, they are a one-way ticket to disappointment.

Is everything becoming AI?

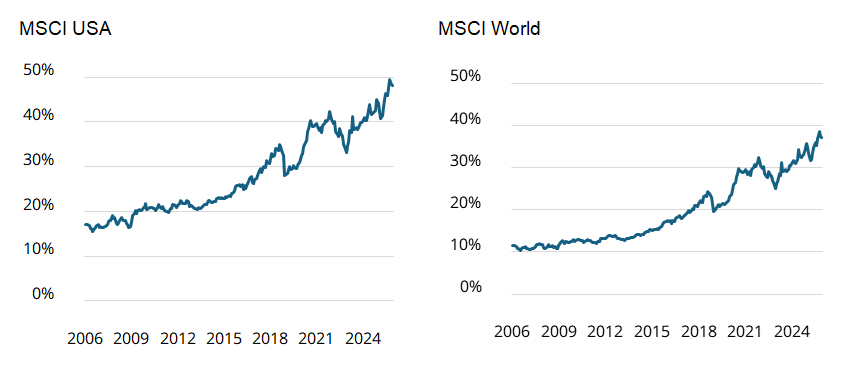

Most investors in US equities have roughly half their money in technology stocks, once you include Amazon and Tesla (Consumer Discretionary), and Alphabet and Meta (Communication Services). That proportion has marched higher in recent years. Nvidia, with its $4.5-trillion free-float market capitalisation and 5.5% weight in the MSCI World index, is now larger than every other developed stock market on the planet.

Given that the US now makes up over 70% of the global developed market, investors in global equities fare little better. Long-held beliefs that a low-cost passive portfolio of global stocks delivers diversification – and avoids having too many eggs in one basket – demand urgent re-evaluation.

Weight of IT sector + Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Tesla

Data to 31 December 2025. Before September 2018, Alphabet and Meta were in the IT sector but sine then they have been in the Communication Services sector. Over the period shown in the charts, Amazon and Tesla have always been in the Consumer Discretionary sectors. Source: LSEG Datastream, MSCI, Schroders

Even this understates things. Here are four additional examples of areas with AI dependency.

Utilities: From defensive plodders to AI‑dependent growth stocks

Utilities have morphed from being a sleepy “defensive” (slow-growth/high-dividend) investment to a growth-oriented sector driven by unprecedented energy demand. The correlation is two-fold: AI requires massive, reliable power, causing utilities to become essential “shovels” in the AI boom, while simultaneously adopting AI to modernise ageing grids. US utilities have risen 25% and 16% in the past two years — almost identical to the tech‑heavy broader US market.

The link with AI is particularly strong for unregulated utilities near to data centre hubs or those with a nuclear component. The top US performers are up 320%, 441%, and 626% cumulatively over the last three years alone. Past performance disclaimers should be flashing brightly at this point.

Meanwhile, dividend payout ratios have been cut (the sector payout ratio is comfortably below its five and 10-year average) as capital is diverted into capex, to meet AI-driven electricity demand. If that demand trajectory disappoints, the sector could face excess‑capacity problems later.

Real estate: data‑centre dependence

Real estate is another sector that in the past investors have turned to for diversification. Here too, AI is becoming entangled. Specialist data centre REITs are one of the largest sectors of the US REIT market. They’re about 10% of the market today vs 4% 10 years ago. Adding in other, more diversified, REITs which have meaningful exposure to data centres pushes that figure closer to 20%. AI demand is embedded deep into the REIT complex.

Software‑driven platforms

There are also other companies such as Airbnb, Uber, Doordash, Netflix, Disney which are software-driven platforms. Their share prices embed an expectation that AI will deliver productivity gains for them (such as content development) and/or an improved user-experience for their customers.

Financials too

Payments companies — established names like Visa and Mastercard and newer entrants such as Block — are structurally tied to online and digital ecosystems. Again: AI exposure.

Put together, investors in US equities have done exceptionally well out of these exposures but now are likely to have a vast, concentrated bet on a technology/AI narrative. This is not simply about correlations going to 1 in a crisis — these are fundamental linkages.

Can you do anything to manage this risk?

The aim here isn’t to claim AI will fail, or even that AI-related companies are overvalued for what they might deliver, but to explore how investors can guard against this risk without giving up equity exposure.

Value equities as a hedge against AI-risk (without sacrificing equity exposure)

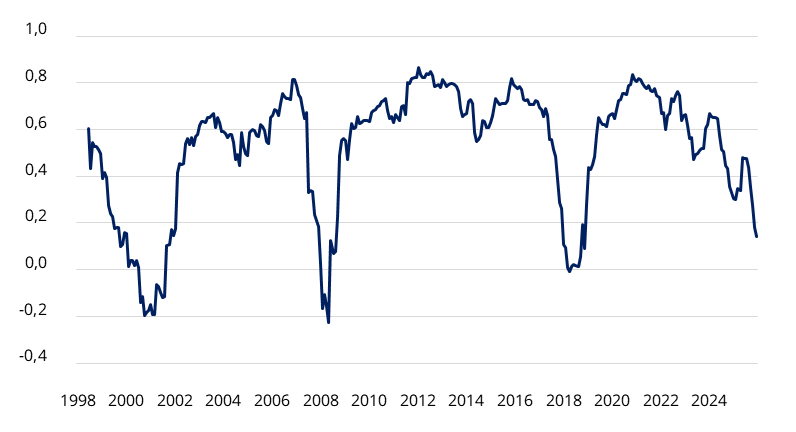

Value investing remains underappreciated in this context. In the US, the correlation between value equities and the “AI trade” — using semiconductors and equipment as a proxy — has recently been low and falling. During the Dotcom selloff it even turned negative.

This suggests value may offer valuable and significant diversification benefits.

Value equities have had a low correlation with AI-stocks

Rolling 24-month correlation: S&P 500 pure value vs S&P 500 semiconductors & equipment index

Value is MSCI pure value total return index, semis are S&P 500 semiconductors and equipment total return index. Semiconductors used as a proxy for AI-stocks. Data covers 30 June 1996 (inception of S&P 500 semiconductors & equipment index) to 31 December 2025. Source: LSEG Datastream, S&P and Schroders.

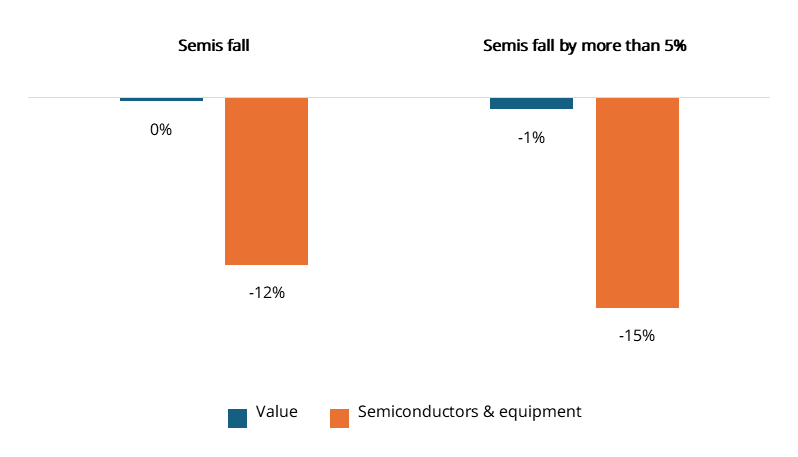

Even more importantly, if we isolate those quarters where semiconductor stocks fell, value equities were roughly flat, on average, versus a 12% average decline for semiconductors. In deeper drawdowns (semiconductors down by 5% or more), semiconductors fell 15% on average. Impressively, value stocks fell only 1%.

Value equities have delivered significantly better outcomes in down-markets for AI-stocks

Median quarterly return in quarters where semiconductors fall

Value is MSCI pure value total return index, semis are S&P 500 semiconductors and equipment total return index. Semiconductors used as a proxy for AI-stocks. Data covers 30 June 1996 (inception of S&P 500 semiconductors & equipment index) to 31 December 2025. Chart isolates those quarters where semis fell in value; non-overlapping periods are used. Source: LSEG Datastream, S&P and Schroders.

One reason for this is the “margin of safety” that value investors benefit from, when buying companies on cheaper valuations. By only paying low prices relative to conservative appraisals of earnings or asset values, investors avoid areas of the market that require large growth to justify the price. So, when those areas of the market that have enjoyed a speculative boom retreat, value investors are often much more immune to those falls.

This analysis is based on US value stocks but, in today’s environment, the case is even stronger for value outside the US. If investors turned off US stocks specifically, because of high valuations or any other reason, US growth and value stocks would likely both suffer (to varying degrees). Non-US value should be more resilient in such a scenario.

The view from the frontline: Simon Adler, Head of Value Equities, Schroders

AI may well deliver, particularly operationally. But as we’ve seen, time and time again, investor returns are often materially different (and frequently worse) than the explosive growth experienced by disruptive new technologies. There are echoes of the dot com era here, in that the explosion of the internet and related businesses and services was indeed revolutionary, but resulted in too much capacity and capital chasing too few opportunities, with disastrous consequences for investors who bought in at peak tech bubble enthusiasm. Value investors did much better in this period, incidentally, which could serve as a useful precedent.

Value investing offers a margin of safety which AI stocks long-ago-abandoned

Value investors tack a different route. A disciplined value selection process will steer investors to precisely where peak market euphoria is not. At Schroders, we screen for, and solely analyse, stocks in the cheapest parts of the market. It’s worth noting this now includes some companies and industries that have already sold off largely because of AI-related fears. So “AI fever” is providing opportunities for us, too!

It takes courage, consistency and a data-led approach to eschew investing in “new paradigms” in which stocks or even entire industries have supposedly reinvented themselves as high-growth, high-returning businesses. Our requirement for a large margin of safety every time we invest steers us well away from some of the sector examples referred to above. We have no issue with investing in utilities, real estate or financials based on a prudent assessment of their earnings power, and we do invest in each of these sectors across our range of strategies. But we will not increase our assumed earnings power, multiples or fair values merely because companies in these sectors are exposed to AI which might deliver in the future.

In our view, many investors, either deliberately or unwittingly (via passive exposure) are sacrificing most, if not all, of their margin of safety by paying up for AI exposure. A disciplined value approach to stock selection, by contrast, will allow for a wide range of outcomes that could still make attractive returns under various scenarios. This is in stark contrast to the range of AI-related themes, sectors and stocks where investors are increasingly pricing these businesses for perfection.

Conclusion

AI may transform everything – or not. What is clear is that most equity portfolios are now running a far larger implicit bet on the AI narrative than investors appreciate. And many of the usual diversifiers have all become entangled in the same theme.

If investors want to reduce their dependence on a single powerful narrative without selling equities, value investing stands out. The historical data show that value has tended to hold up well when the AI trade stumbles. But most passive value strategies won’t help: they are full of the same mega‑cap technology names that dominate the broader market.

If investors want to reduce their dependence on a single powerful narrative without selling equities, value investing stands out.

An active value approach offers a way to maintain equity exposure, reduce AI concentration risk, and build a more resilient return profile. In an investment world increasingly shaped by a single theme, that kind of diversification is worth a great deal.

About the Authors

Simon Adler, Duncan Lamont

Simon Adler is a fund manager and head of Schroders Global Value Team, which manages income, recovery and sustainable strategies across four geographies: UK, European, Global and Emerging Markets. Simon co-manages Global and International strategies.

He joined the Global Value team in July 2016 to manage portfolios. His investment career commenced in 2008 at Schroders as a UK equity analyst.

He was previously sector analyst responsible for Chemicals, Media, Transport, Travel & Leisure and Utilities. He was a Global Sustainability Specialist in Global Equity team until 2016. Qualifications: CFA Charterholder; MA in Politics, Edinburgh University

Duncan Lamont is Head of Strategic Research at Schroders. He writes actionable, thought leadership research to offer insights which help Schroders’ clients make better investing decisions.

His work covers a wide range of topics and asset classes, both public and private. Of particular note is his work on the evolving role of stock markets against a backdrop of declining public company numbers. This has attracted widespread acclaim and been widely covered by the press. Duncan has 19 years of experience.

Prior to joining Schroders seven years ago, he was a principal in the Global Asset Allocation team at Aon Hewitt, where he was responsible for the development of the firm’s long term strategic capital market assumptions, and driving its medium term asset allocation views across the full range of traditional and alternative asset classes. He also had spells as an assistant director at a corporate finance boutique and as a trainee investment consultant.

Duncan is a CFA charterholder with a Masters in Mathematics, Operational Research, Statistics and Economics from the University of Warwick, specialising in actuarial and financial mathematics.

Company website: https://www.schroders.com/en-za/za/intermediary/

Disclaimers:

Important Information

For professional investors and advisers only. The material is not suitable for retail clients. We define “Professional Investors” as those who have the appropriate expertise and knowledge e.g. asset managers, distributors and financial intermediaries.

Investment involves risk.

This information is a marketing communication. The information contained herein is believed to be reliable. Where third-party data is referenced, it remains subject to the rights of the respective provider and must not be reproduced or used without prior consent.

Any data has been sourced by us and is provided without any warranties of any kind. It should be independently verified before further publication or use. Third party data is owned or licenced by the data provider and may not be reproduced, extracted or used for any other purpose without the data provider’s consent. Neither we, nor the data provider, will have any liability in connection with the third party data.

The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on any views or information in the material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

Any references to securities, sectors, regions and/or countries are for illustrative purposes only.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Exchange rate changes may cause the value of any investments to rise or fall. Schroders has expressed its own views and opinions in this document, and these may change.

This document may contain “forward-looking” information, such as forecasts or projections. Any forecasts stated in this document are not guaranteed and are provided for information purposes only.

Schroders will be a data controller in respect of your personal data. For information on how Schroders might process your personal data, please view our Privacy Policy available at https://www.schroders.com/en-za/za/intermediary/footer/privacy-policy/ or on request should you not have access to this webpage.

For your security, communications may be recorded or monitored.

Issued in February 2026 by Schroders Investment Management Ltd registration number: 01893220 (Incorporated in England and Wales) which is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority and an authorised financial services provider in South Africa FSP No: 48998.