Notwithstanding market concentration, relatively high valuations and rising fears about a potential AI bubble, the outlook for global equities isn’t necessarily negative. Positive economic momentum, robust earnings support and structural investment in new technologies may underpin global markets for a while yet.

Another surprisingly strong year

In 2024, against a backdrop of macroeconomic and geopolitical uncertainty, global equities delivered 18% in US dollar terms. In 2025 so far, despite ongoing political volatility, global equity markets have again performed extraordinarily well, producing a return of 20.5% in dollars at the time of this writing.

A number of factors are at work. The US economy remains robust, supported by massive fiscal stimulus (as with the One Big Beautiful Bill Act); high levels of capital expenditure, particularly by big tech companies; solid wage growth; and low energy prices. President Trump’s tariff policies have accelerated inward investment in the US and, so far at least, not led to higher inflation. The overall result has been strong earnings growth: earnings for the S&P 500 are likely to rise by 13% year-over-year overall in 2025. It is not surprising, therefore, that investors have simply looked through the geopolitical noise and focused on the fundamentals.

In the rest of the world, optimism has also prevailed, with both European and Asian markets notching up some of their best returns in many years. The drivers of return have so far been slightly different, however, as economic momentum and earnings growth have been much more muted in both regions. Re-valuation has been the primary factor. Investors are anticipating economic recovery in 2026. Overall consensus estimates are strong: Europe, Asia and the US are now forecast to generate 12-15% earnings growth next year.

Valuations are high but could stay that way (for now)

A valid concern is that markets are already more than discounting a positive growth scenario. Almost all markets around the world look expensive relative to recent history, trading at multiples well above their 15-year medians. Long-term fundamental measures such as the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE) or the market-cap-to-GDP (gross domestic product) measure (favoured by Warren Buffett) are flashing red. The doubters can certainly point to the fact that, historically, markets have always reverted to the mean, and that suggests significant downside from current levels. While that is a risk that rightly looms large in our daily debate, all the market dynamics we have noted here lead us to believe those elevated valuations are sustainable for the time being. Short-term interest rates in many countries are likely to fall, providing support to market multiples, specifically in the US. As confidence levels in economies such as China, India or Brazil begin to improve, there could be strong demand for assets in these markets, particularly given diversified risk exposure.

Structural factors, such as China’s transition to becoming a technology giant (already evident in the electric vehicle, renewable energy and robotics sectors), are also probably being underestimated by the market. Similarly, in Europe, structural drivers such as technology infrastructure and energy transition remain fundamentally underestimated, in our view. All these factors suggest that relatively high valuations can be sustained and could go higher still.

Concentration in itself is not a bad thing

There is understandably much focus on the degree of concentration in equity markets, particularly in the US. The 10 largest technology names now account for around 40% of the S&P 500 market capitalisation, a record high.

Looking back in time, it’s clear that every major phase of innovation has been characterised by prolonged periods of concentration. Unlike previous phases, the current technology-driven innovation wave is composed of multiple innovation cycles, of which the most recent (and most rapid) is evident in the field of large language models, otherwise known as Generative AI.

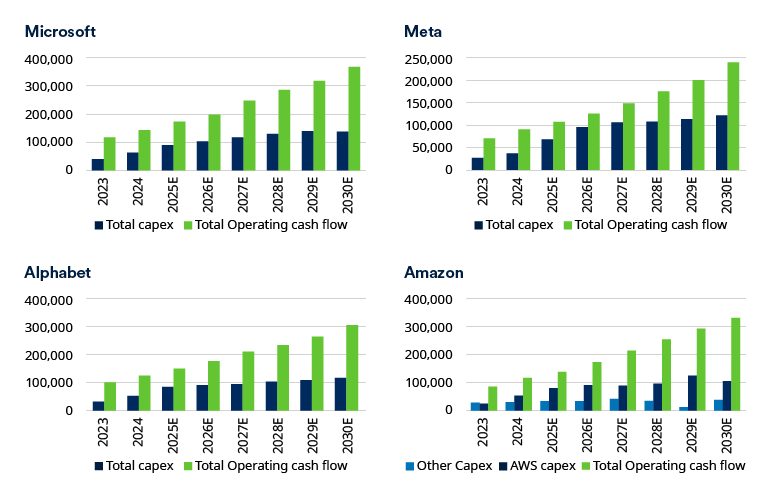

The share price performance of the Magnificent Seven (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla) has been driven by gigantic investment in AI infrastructure. As shown in Figure 1, the rises in capex in recent years represent a relatively small proportion of their operating cashflows. The biggest spenders have scope to increase spending quite a bit further if they deem it appropriate.

Figure 1: The hyperscalers’ capital expenditures may still have room to grow

As the numbers have grown, so, too, have doubts about the likely return on investment and the circularity inherent in the current AI supply chain. With the largest firms accounting for more than 70% of total S&P 500 capital expenditure this year, it is no exaggeration to say that the fate of the US stock market, as a whole, depends on continued confidence in the future of AI.

For now that confidence remains intact. There are some signs of irrational exuberance, as reflected in the outsized performance of AI-related companies with no earnings or even no revenues. However, the total market capitalisation of those companies is small. The much more important question at this point is whether AI models can monetise at a rate that justifies the huge expenditures outlined above. There have been some encouraging signs in this regard, with Google parent Alphabet reporting a material contribution to revenue growth in cloud, search and even YouTube from AI-related deployment.

Interestingly, ChatGPT itself is already generating revenue: about $20 billion in 2025. Based on our analysis, ChatGPT models could generate revenues of $200 billion by 2030. That puts the current $500-billion market valuation of parent OpenAI into sharp context. If the company were listed, a not unrealistic valuation would be 10 times forward sales, implying a $2-trillion market capitalisation. Given that AI-chipmaker Nvidia currently commands a $5-trillion valuation, the enthusiasm for AI investment suddenly becomes quite rational.

Conclusion: Proceed with confidence, invest with caution

Our optimism about the outlook for 2026 doesn’t diminish our awareness of the risks. If as we expect, markets continue to rise, the risk of a major correction by definition becomes more acute. That is particularly true with valuations already at stretched levels.

The old adage that bull markets don’t die of old age is probably as valid today as it has ever been. It implies that there has to be a catalyst for a substantial correction to take place. At the moment, there is no clear catalyst in sight. Sooner or later, however, a catalyst will come along, in our opinion, most likely from the bond market. Trump policies, whilst proving effective in the short-term, are potentially storing up trouble in the form of higher inflation and rampant federal debt. Similarly the UK economy, already struggling to find avenues for growth, may be overwhelmed by the weight of tax-funded government spending, eventually requiring a bailout.

There are multiple other potential catalysts, any of which could precipitate a reset in market valuations to more normal levels. In such circumstances, most assets will do quite poorly. Within equities, there is nevertheless a cohort of unloved, cash-generative and well-funded companies that could do relatively well. Increased exposure to selective healthcare, consumer and utilities stocks will likely offer useful diversification when the correction comes.

About the Author

Alex is currently Co-Head of Equities and lead portfolio manager for diversified global equity portfolios on the Global Equities desk, taking on the role of Co-Head of Equities in April 2024. Alex re-joined Schroders in July 2014 as Head of Global Equities, having commenced his investment career at Schroders in 1990 with responsibility for promoting European Equity mandates alongside Schroders’ Private Equity operation. In 1994 he moved to Deutsche Asset Management Ltd, where he worked in various capacities including Managing Director and Head of International Equities/Portfolio Manager.

He was lead manager of the Deutsche International Select Equity Fund (MGINX) from inception in May 1995. He also previously served as co-manager of DWS International Fund, DWS Worldwide 2004 Fund, Deutsche Global Select Equity Fund and Dean Witter European Growth Fund.

Alex re-joined Schroders in 2014 from American Century Investments in New York, where he worked from 2006 as Senior Vice President and Senior Portfolio Manager (Global and Non-US Large Cap Strategies). He was lead manager of the American Century International Growth Fund (TWIEX) from July 2006 to March 2014. A dual citizen of UK and Switzerland, Alex was educated at Winchester College (UK) and University of Freiburg/Fribourg, Switzerland, where he obtained a Masters’ Degree in Economics and Business Administration.

Company website: https://www.schroders.com/en-za/za/intermediary/

Disclaimers:

Important Information

For professional investors and advisers only. The material is not suitable for retail clients. We define “Professional Investors” as those who have the appropriate expertise and knowledge e.g. asset managers, distributors and financial intermediaries.

Investment involves risk.

This information is a marketing communication. The information contained herein is believed to be reliable. Where third-party data is referenced, it remains subject to the rights of the respective provider and must not be reproduced or used without prior consent.

Any data has been sourced by us and is provided without any warranties of any kind. It should be independently verified before further publication or use. Third party data is owned or licenced by the data provider and may not be reproduced, extracted or used for any other purpose without the data provider’s consent. Neither we, nor the data provider, will have any liability in connection with the third party data.

The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on any views or information in the material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

Any references to securities, sectors, regions and/or countries are for illustrative purposes only.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Exchange rate changes may cause the value of any investments to rise or fall. Schroders has expressed its own views and opinions in this document, and these may change.

This document may contain “forward-looking” information, such as forecasts or projections. Any forecasts stated in this document are not guaranteed and are provided for information purposes only.

Schroders will be a data controller in respect of your personal data. For information on how Schroders might process your personal data, please view our Privacy Policy available at https://www.schroders.com/en-za/za/intermediary/footer/privacy-policy/ or on request should you not have access to this webpage.

For your security, communications may be recorded or monitored.

Issued in January 2026 by Schroders Investment Management Ltd registration number: 01893220 (Incorporated in England and Wales) which is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority and an authorised financial services provider in South Africa FSP No: 48998.