Employees are important stakeholders in any business and our goal is to provide the best working conditions together with the highest remuneration in the industry for all categories of staff.

-Raymond Ackerman and Hugh Herman, Pick n Pay Stores Limited Annual Report 1990

Shoprite’s satisfactory performance is directly attributable to staff commitment, a clearly defined target market and a marketing philosophy of providing customers with the lowest prices. Shoprite has effected its strategic plan of forfeiting a measure of profitability in a continued drive to gain market share.

-Whitey Basson, Shoprite Holdings Limited Annual Report 1990

Background

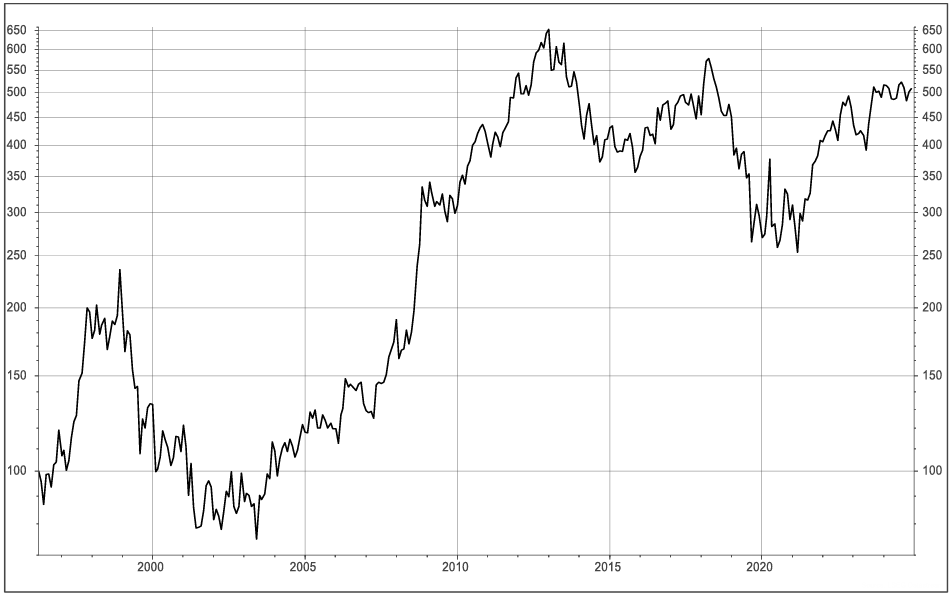

Pick n Pay is a company with a long and illustrious history in South Africa. It was one of the pioneers of modern grocery retail in the country. From a humble start of four stores in Cape Town in 1967, founder Raymond Ackerman built a group with a stellar reputation. The company went public in 1968. On the back of its operational success, the company’s share price did exceptionally well in its first two decades on the stock market. It was undoubtedly the leading food retailer of South Africa in the last decades of the previous millennium.

From the mid-1980’s to the late 2010’s, the company’s share price broadly tracked the South African market. Operationally, the company was delivering mixed results. In 2008, Pick n Pay was voted the world’s best retailer by the US-based National Retail Federation – but by this time the company’s best years were behind it. A fifteen-year period of inconsistent operating results followed, characterised by CEO changes and repeated turnaround efforts. These failed. In 2024, the share price imploded as it became evident that the company was facing real financial difficulties. These proved so severe that the company was forced to raise money from shareholders and sell off a piece of Boxer, the crown jewel in the group.

Chart 1: Pick n Pay total return relative to SA market 1974 – 2024 (rebased to 100, log scale)

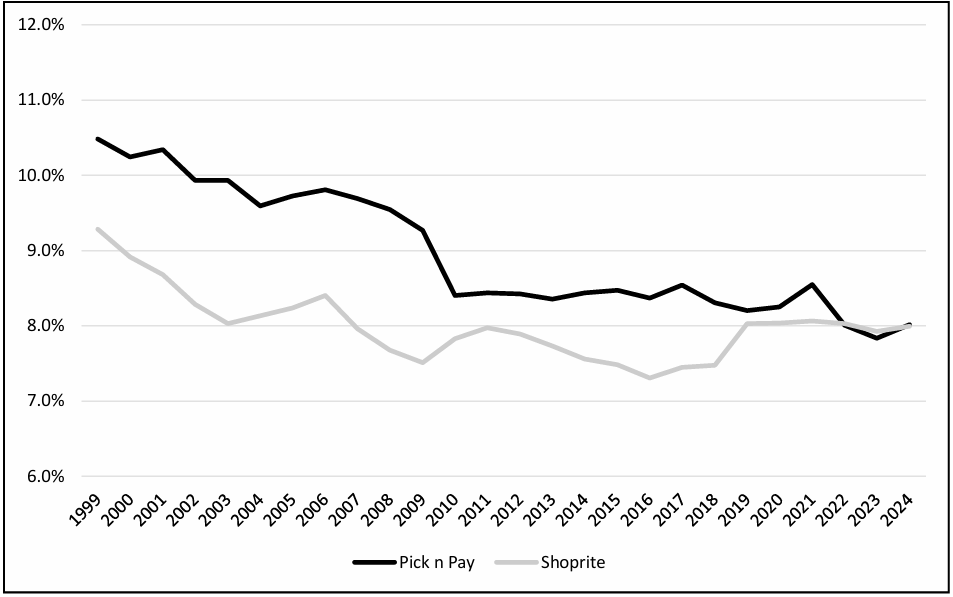

Shoprite came to the South African grocery industry as an underdog. Incidentally also founded in 1967, the business was acquired by the Christo Wiese-controlled Pepkor group in 1979 and listed separately in 1987. Under the stewardship of Wiese and the executive leadership of Whitey Basson, Shoprite grew aggressively, both organically and acquisitively. As much as Pick n Pay had always focused on offering consumers low prices, the target market had been higher income customers. Shoprite focused squarely on the lower income consumer.

Like Pick n Pay, Shoprite’s share price performed very well in the first few years after listing, but then languished until the mid-2000’s. 2003 marked the start of a decade of spectacular share price outperformance for Shoprite. The company grew strongly on the back of an expanding middle class, increased government social welfare programs in South Africa, and growth in Africa. From being a scrappy upstart, the company became the largest food retailer in the country. The share price has tracked the SA market since the mid-2010’s, but relative to the rest of the industry, Shoprite has continued to go from strength to strength.

Chart 2: Shoprite total return relative to SA market 1997 – 2024 (rebased to 100, log scale)

Pick n Pay vs Shoprite

Grocery retail at scale is an attractive business. The combination of bargaining power with suppliers and lower unit costs of distribution that come with market leading scale creates a business that can generate good economics for shareholders for very long periods of time. Both Pick n Pay and Shoprite have had such scale for decades. Yet for shareholders, Pick n Pay has been a disaster and Shoprite has been a success. Why? And, more importantly from an investor’s perspective, were there advance warnings that Pick n Pay as an investment was going to be the disappointment that it has been? We read through 35 years of annual reports and investment research on the two companies to find out.

A quick word of caution before we proceed. We are writing this with the benefit of hindsight. It is human nature to convince oneself that facts which appear significant in hindsight, would also have been considered significant at the time that they were first evident. There can of course be no such assurance. As much as we strive to evaluate past events in a clinically objective way, it is difficult to refrain from having one’s assessment coloured by subsequent outcomes. A supremely risky strategy that happens to succeed is in hindsight likely to be admired and considered an obvious path to success. Likewise, a sensible strategy that happens to fail is likely to be scoffed at. Yet in business, the range of potential outcomes for any strategy pursued and decision made is wide and cannot be judged solely on the outcome thereof. Keeping all of this in mind, we found the following notable in our study of the success of Shoprite and the predicament of Pick n Pay.

Governance

Besides being founded in the same year, Pick n Pay and Shoprite have another peculiar aspect in common: control structures.

In the case of Pick n Pay, the Ackerman family has controlled the group since inception, initially via a listed holding company, and later via a special class of high voting shares. The Ackerman family also retained the right to appoint the chair, chief executive officer and chief financial officer of the group. This control is being forfeited as part of the capital restructure Pick n Pay embarked on in 2024.

In Shoprite’s case, Wiese exercised outright (i.e. greater than 50%) voting control of the company via a special class of deferred shares for many decades. His voting rights have fallen below 50% in recent years, but still far exceeds his economic interest in the group.

Family control of a company is usually considered a positive attribute. Unsurprisingly, the Ackermans often espoused this view.

Our focus on the business as family controlled and run has been vindicated throughout the years. Shareholders will know that I have repeatedly stated why I believe this is the best possible way to sustain a business. Uppermost amongst these virtues is the focus on values and principles. The comfort of being able to withstand the pressure to perform financially while retaining the essence of solid values is not the exclusive preserve of family run businesses, but it does tend to represent a defining characteristic of them.

-Raymond Ackerman, Pick n Pay Stores Limited Annual Report 2003

The Ackerman family has directed and overseen significant change in the business since inception, but especially over the last five to six years. Only recently has the subject of competitive advantages of businesses controlled by family shareholder control groups become a topic in the corporate finance literature. Family-controlled firms are more inclined to have a long-term perspective, conservative financial management, and a strong corporate culture, all attractive attributes conducive to long-term share outperformance. This is a view strongly supported by Warren Buffett and others. Mark Zuckerberg follows the same strategy, stressing that being founder led has helped Facebook resist the short-term pressures that often hurt companies. As he points out, this also gives the company the freedom to prioritise and take decisions that don’t always pay off right away, but are in the long-term interests of both shareholders and communities. Importantly, a recent study in the US showed that of the top ten performing supermarkets in the US, eight out of ten were founder, family or employee-controlled companies. We believe that the continued involvement of the Ackerman family is in the long-term interests of Pick n Pay.

-Gareth Ackerman, Pick n Pay Stores Limited Annual Report 2016

The subject of family control receives essentially no attention in Shoprite’s shareholder reports. The only meaningful communication in this regard was in 2019 when Wiese – allegedly in an uncomfortable financial situation at the time – attempted to sell his deferred shares back to the company for more than R3 billion. Shareholders balked, and the proposal was cancelled.

The arguments proffered in favour of family control have merit. Research suggests that listed companies controlled by a family do tend to deliver above average financial results[1].

The evidence on what this implies for shareholder returns is somewhat mixed though. At least one study suggests that family controlled listed companies deliver superior – and lower risk – stock market returns than other companies[2]. Other studies conclude that family ownership is not a meaningful determinant of stock market returns[3].

What was however (unsurprisingly) not pointed out in any Pick n Pay shareholder communication over the years is the evidence that suggests that the performance of family firms falter dramatically after the first generation[4]. This appears to be due to a pattern of much more conservative strategic decision making enacted by successor generations. Successor-led firms tend to invest less in research and development and pay out more dividends than founder-led firms. The entrepreneurial flair and risk appetite of the founder seems to be lost on the offspring – to the detriment of the business. This adverse impact goes so far as to turn the tables on the impact of family control: successor-led firms underperform non-family firms.

Interestingly, the benefits of family control appear greatest at relatively modest levels of shareholding.

As the ownership stake increases (25%–50%), such that owners can exert full control over the firm (usually with the help of pyramidal equity schemes), the effect on performance becomes negligible and insignificant. We conjecture that at these intermediate levels of concentrated ownership, the positive effects to firms of having a concentrated owner are offset by increased opportunities for self-dealing. At even higher levels of ownership (50%–100%) the effect on performance increases again but remains insignificant. In sum, performance is non-monotonically related to ownership.

-Heugens, P.P., Van Essen, M. and (Hans) van Oosterhout, J., 2009. Meta-analyzing ownership concentration and firm performance in Asia: Towards a more fine-grained understanding. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26, pp.481-512.

Companies where control is entrenched with dual class voting structures are viewed unfavourably by the market: such companies trade at a significant discount to companies without control structures[5]. Evidence on how this affects financial performance of such companies is scant. But the reason for this embedded market value discount is understandable: non-controlling shareholders fear self-dealing by the controlling shareholder at their expense. And here evidence suggests that the fear is justified in the case of family-controlled firms. Family controlled firms are more likely to engage in self-dealing than firms controlled by other types of investors (e.g. governments or large corporates)[6].

Bringing this back to Pick n Pay and Shoprite: family involvement in Pick n Pay has always been far more integral to the character of the business than for Shoprite. The Ackermans served in a wide variety of both executive and non-executive roles in the business for its entire history. Wiese, and in recent years his son, have always only served on the Shoprite board in a non-executive capacity. Shoprite has remained founder led. Raymond Ackerman retired from the Pick n Pay board in 2010. It then became a successor-led business and unfortunately appears to have followed the same path of financial underperformance that many successor-led firms have been down in the past.

Management

Shoprite stands out as having only had two CEOs since Wiese acquired control of the business: Whitey Basson from inception until 2017, and internal appointee Pieter Engelbrecht subsequently. Basson is rightly revered for building Shoprite into the juggernaut that it is. Engelbrecht has done an admirable job of building on the foundation laid by Basson.

Pick n Pay, by contrast, has undergone five changes of CEO since its founding. Raymond Ackerman relinquished the CEO role to Sean Summers in 1999. Summers made way for Nick Badminton in 2007. Both Summers and Badminton were long-serving employees of the company when they were appointed CEO. The transition from Summers to Badminton was smooth. Both were praised in the company’s annual report for the contribution they had made to the group during their tenures. Badminton was hailed for having played ‘a critical role in transforming the business’[7].

Despite these words of praise, the departures of both Summers and (especially) Badminton occurred under circumstances when the business had not been performing as well as it should have. Pick n Pay’s subpar performance relative to Shoprite had already become evident by the mid-2000’s. In his chairman’s letter of 2007 (shortly after Summers’ departure), Ackerman notes that ‘…while we have delivered consistently on price, (our customers’) perception is not necessarily aligned’[8]

The handover from Summers to Badminton happened amid a strategic rethink facilitated by the management consultancy Bain. When Badminton left the group, performance had deteriorated further, and there was no successor to step into the CEO role. Gareth Ackerman (founder Raymond’s son) took over as acting CEO whilst the search for a permanent candidate was underway.

The two executives who came after Badminton were interesting choices. Both were external recruits from the European food retail industry. The first, Richard Brasher, came from Tesco. He had served in very senior positions in Tesco for a long time. His last role at Tesco was that of head of the UK business. When Brasher left Tesco, the UK business was in disarray. It had come off several profit warnings and had been losing market share for years. Brasher’s successor, Peter Boone, came from Metro, where he had been responsible for the Russian business of the group. He left Metro after a period of very weak performance by the Russian business. Weak business performance is at times not only attributable to weak leadership. But the past performance of the businesses with which Brasher and Boone were most closely associated prior to joining Pick n Pay certainly were reason enough to raise an eyebrow or two at their appointment.

Brand strategy and positioning

Shoprite’s emphasis on low prices has always been clear. The 1987 annual report put this front and centre:

The Shoprite chain of 31 supermarkets has, as its target market, the broad lower to middle income group. Its emphasis is on providing a range of food and non-food products at the lowest prices in the cleanest stores, on a cash and carry basis.

-Shoprite Holdings Limited Annual Report 1987

The acquisition of Checkers in the early 1990’s precipitated a move into a higher income target market. But the group created a clear distinction between the Shoprite brand with its emphasis on low prices, and the Checkers brand, where quality was of greater significance.

We believe the disparity between the highest and lowest LSM consumers in South Africa to be so large that their needs in terms of food retailing cannot be met through a single retail model. For this reason we operate three distinct formats in Shoprite, Checkers and Usave, and for each we have developed a different offering and supply chain to match the specific needs and aspirations of the target markets involved.

-Whitey Basson, Shoprite Holdings Limited Annual Report 2013

Pick n Pay adopted the concept of consumer sovereignty as the cornerstone of its business[9]. This comes across as somewhat more nebulous than Shoprite’s clear and simple low-price strategy. And Pick n Pay attempted to serve a very broad spectrum of customers with one brand. The quote below is from Richard Brasher’s first report to shareholders after his appointment – incidentally, like the quote from Whitey Basson above, also published in 2013.

Commentators on the retail sector often speculate on whether a business occupies the higher, middle or lower ground in their appeal to customers. This is a false debate. The key to success in retail – and the heart of any good business – is to appeal broadly, to exclude nobody, and to move hand-in-hand with customer needs and aspirations. I believe Pick n Pay, with its rich history of inclusiveness and its deep well of customer loyalty, is uniquely positioned to do this in South Africa.

-Richard Brasher, Pick n Pay Stores Limited Annual Report 2013

Whilst there certainly are examples of large retailers successfully serving customers across very broad income levels (Costco in the United States and Tesco in the United Kingdom come to mind), Shoprite’s assessment of the right brand strategy for a food retailer in the South African context appears to have been more accurate than that of Pick n Pay.

Cost structures

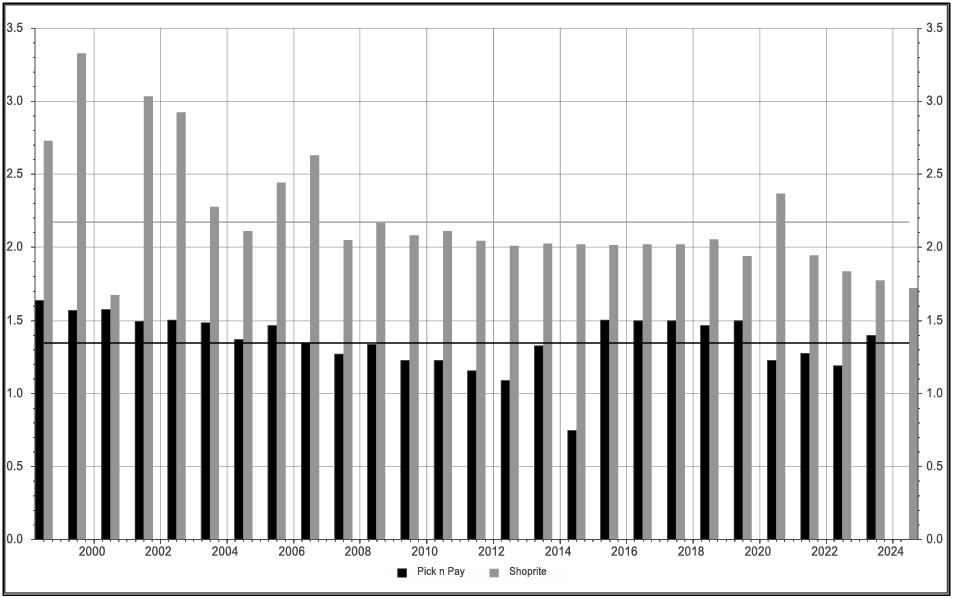

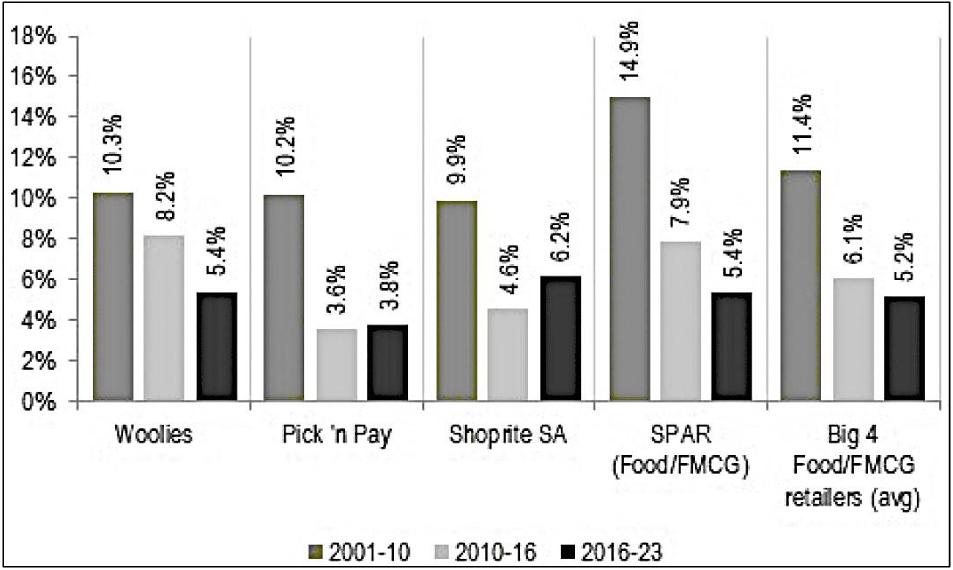

Food retail is a low margin business. The key to long term success is moving large volumes of goods from suppliers to customers as efficiently as possible. Keeping costs low is of existential importance. The three critical costs in the business are cost of goods, store costs, and employee costs. Historically there appears to have been little distinction between Shoprite and Pick n Pay on the former two cost categories. But when it came to employees and employee costs, there has been a clear difference.

Pick n Pay always emphasised how well it looks after employees. This piece’s opening quote from the Pick n Pay Annual Report from 1990 illustrated the point. But the emphasis on paying and treating staff well did not have the expected outcome of exemplary labour relations for Pick n Pay. The company suffered as many (if not more) strike actions than Shoprite over time, including a particularly severe one in 1994.

Where Pick n Pay’s remuneration policy unfortunately did have the expected outcome was in its impact on the company’s cost structure. By 2011, average remuneration per employee for Pick n Pay was R120,000 per year, compared to R60,000 for Shoprite[10]. During the 2000’s, employee costs as a percentage of revenue was about 1.5% higher for Pick n Pay than for Shoprite. In a business where operating profit margins hover between 2% and 5% for well run businesses, this difference is vast.

Chart 3: Employee cost as percentage of revenue

Whilst the chart above suggests that Pick n Pay has managed to address some of this employee cost discrepancy in recent years, it is worth keeping in mind that wholesaling to Pick n Pay franchisees is a far more material part of Pick n Pay’s business than it is for Shoprite. Wholesaling is far less labour intensive than store-based retail. So even in recent years, when comparing Pick n Pay’s corporate stores (i.e. excluding franchise operations) to Shoprite, Pick n Pay has still incurred a far higher employee cost ratio, and has generated far lower sales per employee, than Shoprite[11].

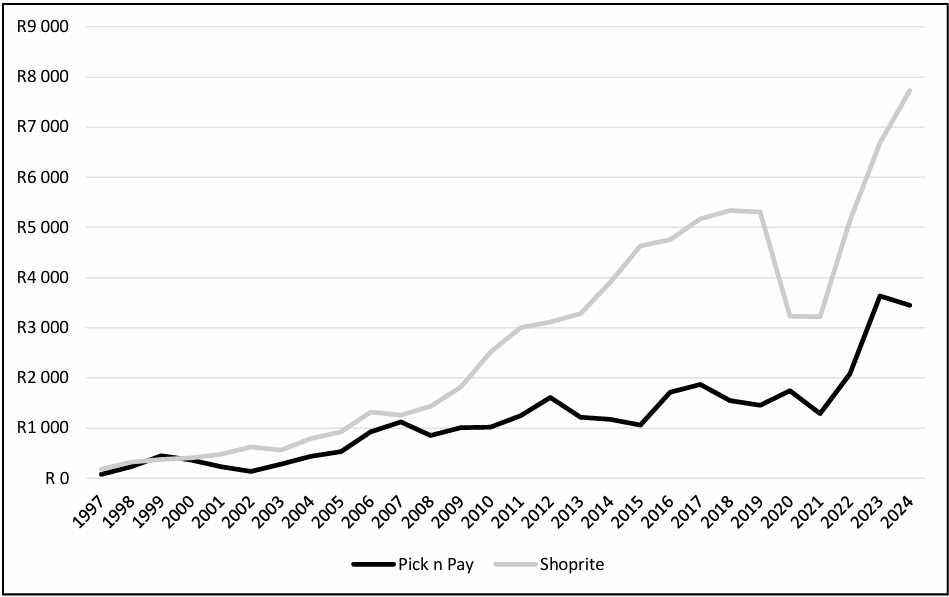

Capital allocation

When executed well, food retail is a famously capital light business. Customers pay in cash when a sale is made, and suppliers – with limited bargaining power against the behemoth of a customer that is a leading food retailer – extend generous payment terms. This means inventory is turned into cash before payment to suppliers is due. The result is fantastic cash generation. The matter of how to apply this cash then becomes of prime importance.

Shoprite historically chose to invest aggressively in expanding and improving its operations. It was an early mover into centralised distribution. It rolled out stores at pace and pursued aggressive growth in numerous African markets. These actions all required substantial investment – often in properties, when it wanted to expand in areas where there was not an established stock of rental properties from which it could operate its stores.

The push into Africa boosted growth in the 2010’s but eventually ran into numerous macro-economic headwinds. This prompted a retreat from several of these markets. The objective stated in the 2003 Annual Report of achieving more than 50% of earnings outside of South Africa in the medium term was never close to being achieved.

The investment in centralised distribution and store expansion in South Africa paid off handsomely though. Greater efficiency in distribution allowed Shoprite to achieve exceptional profit margins while maintaining price leadership. Lower cost structures made more store locations viable which increased market share and scale, which in turn drove economies of scale even further. The lower returns on invested capital that came along with this capital-intensive growth strategy was a price well worth paying.

Pick n Pay on the other hand, was far less aggressive in its capital expenditure. Like Shoprite, the company ventured outside of its South African home market: after some early unsuccessful forays into the country, it acquired Franklins in Australia in 2001. As is so often the case, this was done when Pick n Pay was enjoying great success in its home market. It was also a time of great general negativity towards South Africa and emerging markets, and a dramatically weak Rand.

For many years, questions were asked of Pick ’n Pay’s ability to grow strongly into the future, given our cash resources and no clear plans to utilise them for new business opportunities. Our philosophy always was that the time to make a significant local or overseas acquisition would be in one of strength and I certainly believe that our ability to absorb the start-up costs in Australia this year, and yet achieve the overall result for the year ended 28 February 2002, is a mark of enormous hard work and dedication from all parties concerned. We need to furthermore bear in mind that post our acquisition in Australia, the start-up costs that we have had to endure have increased in SA Rand terms by 50% purely on currency devaluation. This obviously counts strongly in our favour from an investment perspective and when we start to generate profits. As is natural, our acquisition in Australia has raised many questions as to the prospects for success in the future. It is our considered opinion, that we have duly weighed up all of the risks and opportunities that present themselves in this new business venture. We are confident that the next 12 to 24 months will help us gain a working knowledge of the Australian market so that in the future there will be an ever-increasing portion of our earnings from offshore, through our Australian operation.

-Sean Summers, Pick n Pay Stores Limited Annual Report 2002

Like Shoprite, Pick n Pay’s offshore investments would prove a disappointment. The Australian business was sold for a modest amount of money in 2011.

However, shortly after the acquisition of Franklins, Pick n Pay had made a far smaller acquisition, this time in South Africa: Boxer. Boxer was a discounter focused on the lower income consumer. It would prove to be an inspired acquisition. Left to operate independently under a stable management team, Boxer delivered stellar results for the next twenty years. It grew into a hugely valuable asset for Pick n Pay. Without Boxer in its stable, it is questionable whether Pick n Pay would have been able to execute the capital restructure of 2024 or survive in its current form.

When it came to organic growth, instead of spending capital as aggressively as Shoprite, Pick n Pay chose to maintain a very generous dividend policy. From 1998 to 2024, Pick n Pay’s average dividend cover was about 1.3 times. For Shoprite, it was more than two times.

Chart 4: Pick n Pay vs Shoprite dividend cover 1998 – 2024

Whereas the two companies incurred comparable amounts of capital expenditure per year in the late 1990’s, Shoprite started to outspend Pick n Pay dramatically in the ensuing years – especially from the late 2000’s onwards.

Chart 5: Capital expenditure (R’m)

Sales growth and market share

For Pick n Pay, questionable governance and CEO appointments, a brand message lacking clarity, bloated cost structures which limited the company’s ability to compete on price, and insufficient investment in the core business all combined to create a group seemingly beset by sclerosis. Sales growth – both overall and on a same stores basis – lagged that of Shoprite.

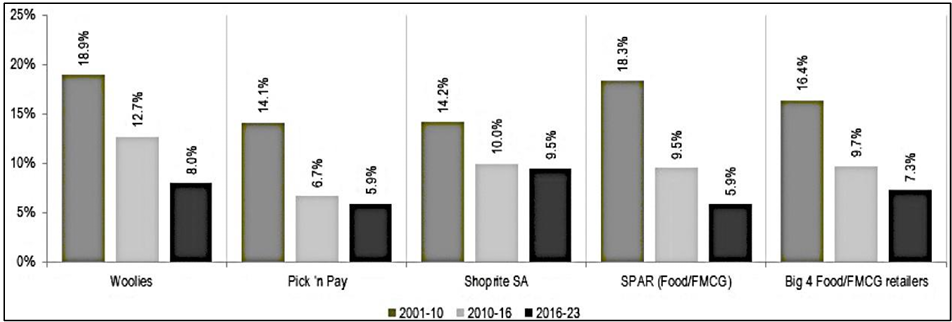

Chart 6: SA food retailers total sales growth 2001 – 2023

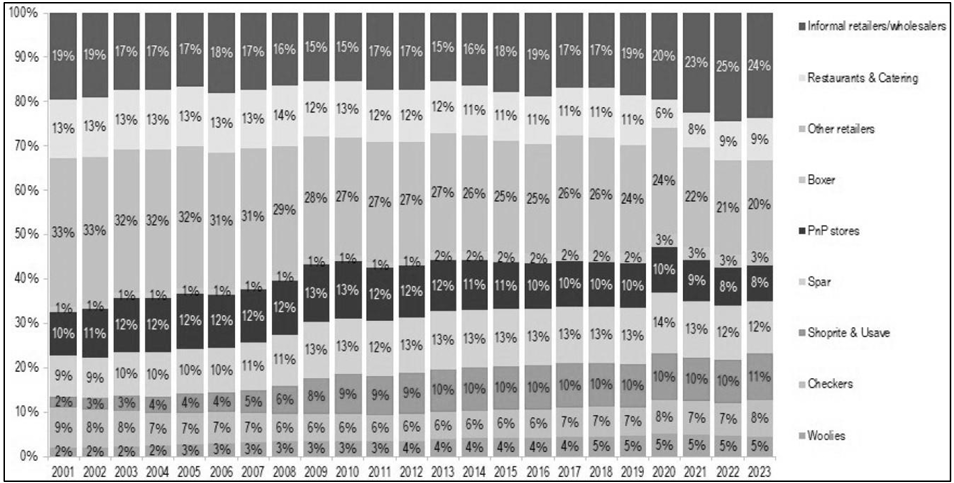

Slow sales growth translates into a loss of market share – if not in absolute, then certainly in relative terms. From 2001 to 2023 market share of the group (Pick n Pay and Boxer combined) remained at 11% of the total South African food market, whereas the Shoprite group grew share from 11% to 19%. A loss of market share eventually diminishes the benefits of scale that a large food retailer depends on to generate the favourable economics associated with the business – though we don’t think Pick n Pay ever reached a critical tipping point on this front.

Chart 7: SA total food market share 2001 – 2023

Weak same store sales growth can be particularly problematic in retail. A store’s costs (mainly rent and employee costs) typically increase at inflationary rates. If the store’s sales growth does not at least keep pace with inflation, profitability is increasingly under pressure. Inflation in South Africa averaged about 5% from 2010 to 2023. As Chart 14 shows, Pick n Pay’s same store sales lagged inflation for this period. The result was a corporate store base that eventually became loss-making.

Chart 8: SA food retailers same store sales growth 2001 – 2023

Conclusion for investors

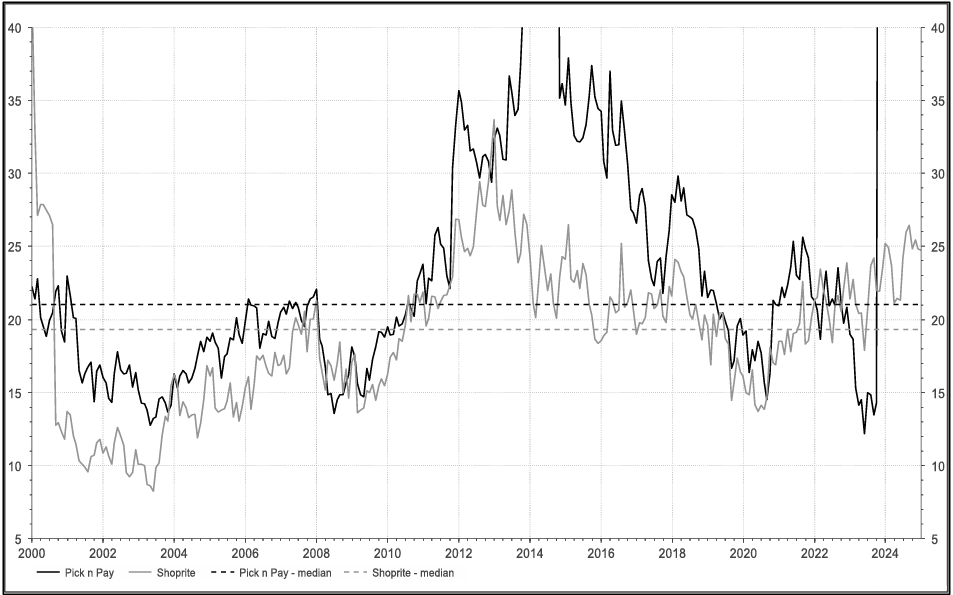

The characteristics of the two companies we discussed above were clear for all to see over the years. Shoprite was demonstrably delivering superior operational results than Pick n Pay. Ordinarily, this will be reflected in share prices. But surprisingly, this was not the case. Shoprite persistently traded at a modest price earnings ratio discount to Pick n Pay over the years.

Chart 9: Price earnings ratio history

Why this apparent anomaly? In our opinion, the following are the most likely reasons for the market getting things so wrong:

- Pick n Pay was better at converting earnings into cash than Shoprite. This was mainly due to the less aggressive capital expenditure. All else being equal, better cash conversion does justify a higher earnings multiple for a share.

- The market liked the strong dividend payments from Pick n Pay. The adverse impact these were having on the long-term competitiveness of the business was only partially appreciated. In contrast to the price earnings ratio, Pick n Pay historically traded at a higher dividend yield than Shoprite – a reflection of the fact that the market did not consider the dividend streams from the two companies as having equal prospects of growing and/or being sustained.

- Shoprite reported very high operating profit margins from the mid-2000’s onwards. There have been many examples of food retailers globally where such high profit margins proved unsustainable. There was likely some doubt in the minds of investors as to how sustainable these margins would be for Shoprite.

Rozendal funds have never had any exposure to either Shoprite or Pick n Pay. We have not been oblivious to the two companies over time, and in our investing careers there have been times when our clients did own shares of either Pick n Pay or Shoprite. As much as we appreciate the difficulty of business turnarounds (and Pick n Pay has been in perpetual turnaround for most of the past fifteen years), we were also hesitant to assume that Shoprite will manage to sustain its world leading profit margins. This limited the appeal of the company’s shares. To Shoprite management’s credit, those high profit margins have endured. We continue to follow both companies with interest and remain alert to investment opportunities that may arise in the shares of these two stalwarts of the South African economy.

If you would like to know more about the Rozendal investment process, funds and availability, visit our website or contact Eugene Taljaard on eugene.taljaard@rozendal.com .

Sources:

- [1]Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W., 1997. A survey of corporate governance. The journal of finance, 52(2), pp.737-783; Boyd, B.K. and Solarino, A.M., 2016. Ownership of corporations: A review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 42(5), pp.1282-1314; Anderson, R.C. and Reeb, D.M., 2003. Founding‐family ownership and firm performance: evidence from the S&P 500. The journal of finance, 58(3), pp.1301-1328; van Essen, M., Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E.R. and Heugens, P.P., 2015. How does family control influence firm strategy and performance? A meta‐analysis of US publicly listed firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(1), pp.3-24.

- [2]Refer for instance to ‘UBS Q-Series: Why do Family-Controlled Public Companies Outperform? The Value of Disciplined Governance’, 13 April 2015.

- [3]Miralles-Marcelo, J.L., del Mar Miralles-Quirós, M. and Lisboa, I., 2014. The impact of family control on firm performance: Evidence from Portugal and Spain. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(2), pp.156-168.

- [4]van Essen, M., Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E.R. and Heugens, P.P., 2015. How does family control influence firm strategy and performance? A meta‐analysis of US publicly listed firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(1), pp.3-24.

- [5]Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Fan, J.P. and Lang, L.H., 2002. Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. The journal of finance, 57(6), pp.2741-2771.

- [6]Solarino, A.M. and Boyd, B.K., 2020. Are all forms of ownership prone to tunneling? A meta‐analysis. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 28(6), pp.488-501.

- [7]Pick n Pay Annual Report 2012

- [8]Pick n Pay Annual Report 2007

- [9] Pick n Pay Stores Limited Annual Report 1990

- [10]Source: Avior Research November 2011

- [11]Source: RMB Morgan Stanley 10 August 2021

Important information

This article contains information owned by third-party providers, which ROZENDAL has been licensed to use under strict usage conditions. Redistribution or reproduction, in whole or in part, without the consent of the third-party provider is not permitted. Third-party license providers shall not have any liability for any errors or omissions contained in the information.

ROZENDAL PARTNERS (PTY) LTD (“ROZENDAL”) is an authorised financial services provider (FSP 48271) in terms of the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (Act No. 37 of 2002).