“This time it’s different” are probably the four most famous and dangerous words in investing. Whenever something dramatic happens in the world, and investment markets respond, whether up or down, investors generally justify their knee-jerk reactions to such movements with the words, “This time it’s different”. Importantly these words can be used to justify decisions to invest or disinvest.

When markets rise investors want a piece of the action

In the technology bubble of the late 1990s, investors justified investing at never-before-seen valuations of businesses, because they believed that the Internet was the harbinger of a new world, and therefore businesses could not be valued on traditional “old economy” metrics. This meant that what were known as “new economy” or “dot-com” businesses were being valued on their revenue growth rather than their profit growth. Investors were valuing businesses that had never made a profit at outrageous levels. If they were bringing in revenue, that’s all that counted. What was “different” now, was that “profit” was an outdated measure of a business’ financial performance. Global stock markets reached stratospheric levels on the “This time it’s different” approach.

Yet in March 2000, the technology bubble burst, and all the so-called, “This time it’s different” stocks came tumbling down. It seems that to grow real value, at some point businesses need to make money. This is not to say that nobody made money during the technology bubble. During any bubble, usually the early investors make money, if they get out before the bubble bursts. We see this playing out 30 years later with cryptocurrency. Some people have made money trading cryptocurrency and others have lost it.

When markets fall investors want to run to the exit

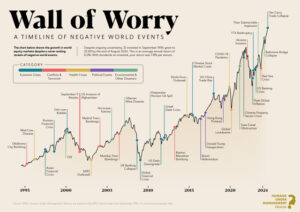

Investors are also prone to poor decision-making when markets fall. Particularly for an extended period. The graphic below, the Wall of Worry, outlines many events that precipitated a fall in global investment markets, whether it was the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York, the global financial crisis of 2008, the Covid-19 pandemic or the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Again, investors react to these events, usually by selling their investments and seeking the safety of cash because they perceive that the world as we know it has ended. In other words, “This time it’s different”.

Benjamin Graham, author of The Intelligent Investor, and mentor to Warren Buffett, offers a simple explanation why investors behave this way. He said, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine,” and people very often vote unintelligently but over the long term it’s the weight of companies and economies that ultimately determine the returns to investors. The problem is, when investors vote unintelligently by buying overpriced assets or selling underpriced assets, they are guaranteeing that they won’t benefit from the weight of the companies they have invested in.

What drives unintelligent voting (investing)?

There are three key factors that drive “unintelligent voting”, which I have labelled as the three sides of the “Bermuda Triangle of Financial Behaviour”. Falling foul of one or more of these factors invariably leads to financial loss.

- Firstly, as social creatures, human beings are influenced by what other people do. When markets are going up, we want to be part of the action. We don’t want to be left out. Our social desire is to “flock” together. And when markets go down, we “flee” together.

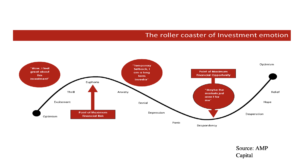

- Secondly, emotions are often a key driver of investor behaviour. When markets go up, we get greedy and when they fall, we get fearful. But our emotions are more complex than that, as the graphic below, The Rollercoaster of Investment Emotion, shows. When markets rise, we can move from optimism, through excitement to euphoria. When they fall, we can go from anxiety, through denial and depression to panic and despondency.

- Thirdly, while humans think they are rational creatures, we are cognitively flawed, and psychologist Hebert Simon argues we have “bounded rationality”. We can see this in the Rollercoaster of Investment Emotions graphic, at the point of Maximum Financial Risk, investors want to buy and at the point of Maximum Financial Opportunity they want to sell. Another word that can describe this behaviour is “irrational”.

Our brains are designed to keep us safe. They are also the operating machine that processes all the information that comes our way daily. But our brains are lazy. In processing information, the brain takes shortcuts, which is the source of the many cognitive biases we fall foul of. So, when the AMP graph is going upwards, it’s not only our emotions that are influencing our actions, but also our brain. It is extrapolating that the upward trend will continue, simply because of recency bias, and the fact that the brain is a pattern-seeking device.

When it comes to our money, we often have an action bias, believing that doing something is better than not. Disinvesting and putting our money into cash feeds this action bias, as well as our present bias which arises from the difficulty for our brains to look far into the future. Our brain wants to keep us safe now. So, we compromise our long-term financial health by acting on our cognitive biases.

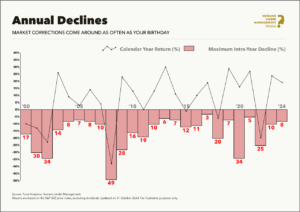

The risk of seeking safety when our brain perceives a threat from a negative return is shown in the graphic below showing annual declines on the S&P 500 over the past 25 years. As can be seen, every year the S&P 500 has been in negative territory during the year, with negative annual returns of over -20% in two years (2003, 2022) and almost -40% in 2008. Yet the index had positive returns in 18 out of 25 years, with an average annual return including dividends in $US of 7% pa for the period.

What can we do to improve our approach to investing?

The Wall of Worry graphic reminds us that there will always be reasons to invest or disinvest. One could look at the graphic and see that when a dramatic event happens, in time this will just be a blip on the Wall of Worry. Sadly, this is unlikely to prevent self-sabotaging behaviour from investors. Certainly, it will help provide an investor with perspective, and this may be helpful as a reminder that perhaps “This time it’s not different”.

But human behaviour has shown itself to be unresponsive simply to information. For the past 30 years Dalbar Inc has conducted research annually on investor behaviour and shows that investors continually sabotage themselves. For the calendar year 2023, the S&P 500 Index returned 26.3% but according to Dalbar the average equity investor achieved 20.8%, an underperformance of 5.5%. Over the longer term, this investor gap has been lower at around 3.6% pa which means that since 2000 the average $US equity investor has achieved long-term equity returns less than 4% pa, rather than the 7% pa return achieved by the S&P 500 since 2000. Why? Because they have responded to many of the events listed in the Wall of Worry graphic. Disinvesting at the wrong time. Re-investing at the wrong time and incurring significant costs in the process.

This poor investor behaviour is despite the investment industry spending millions on ongoing investor communication and education. Simply providing investment education and information to influence investor behaviour is not enough. We have seen that there are multiple factors, social influences, emotional responses and cognitive mistakes that lead us astray. So, it appears we need more than information or education to adjust our behaviour.

Nudging investors seems more effective than educating them

According to Richard Thaler (Economics Nobel Prize winner) and Cass Sunstein, authors of the book Nudge, we need to find ways to nudge people’s behaviour because offering information is not enough. In their book they relate the story of the men’s public toilet at Schiphol Airport, which had a problem with spillage at the men’s urinals. Despite ongoing efforts to address this problem with posters in the doorways and on the walls imploring the users of the toilets to be considerate to others, and warning of the hygiene dangers of spillage, there was no shift in the behaviour of the users of the men’s urinals. Finally, instead of pleading for a change in behaviour, a decision was taken to nudge the men into a change. A fly was painted into the basin of each urinal. Suddenly rather than appealing to men’s cognitive reasoning, a target was provided for them to aim at in the urinal. The spillage problem was solved literally overnight. What can we learn from this story and apply to investing?

It is about the power of a nudge. The key characteristic of a nudge is that it doesn’t require you to think about your action, which is very appealing to our lazy brains. If you’ve ever driven your car home and wondered how you got there, it’s thanks to your brain loving to work on autopilot so that it doesn’t have to use up the energy to think. How can investors nudge themselves into improved behaviour that is not self-sabotaging?

The most obvious way for us to avoid acting when the Wall of Worry hits us is to have an automated investing process, which means that our decisions are not dependent on our thoughts, emotions or social pressure. A good example of an automated process is when we invest via debit order. The decision to invest does not depend on anything other than the date of the debit order run. Similarly, an automated redemption instruction operates on the same principle. Investors who have a living annuity are effectively disinvesting once a month, and this is not dependent on what is happening in the markets. So, a nudge is a way to help us invest or disinvest irrespective of what is going on in markets and depends more on our own circumstances.

Pre-commitment: a way to keep the Wall of Worry at bay

The real power of a nudge is that it provides a pre-commitment to an action, no matter what is going on around you, whatever the Wall of Worry is throwing at you or wherever you find yourself on the rollercoaster of emotion.

By anticipating when clients are likely to experience emotions in response to a Wall of Worry event, financial planners can prepare clients for what they are likely to feel when the going gets tough and help them develop a plan to prevent them from acting on their emotions in the heat of the moment or responding to social pressure or making a cognitive mistake.

The formal act of pre-commitment is key. In the context of financial planning and investing, any form of verbal pre-commitment carries no weight unless it is documented and signed. The form of the document may vary according to the financial planner’s advice process, but clients could sign one or more of a financial plan, a record of advice or an investment policy statement. Whatever the document is, it should ideally include the behaviour the client commits to in the future, given a set of possible circumstances.

As the Wall of Worry suggests, there will always be events that trigger emotional, cognitive or social pressure to invest or disinvest. The Dalbar study shows that successful investing involves being able to resist these triggers, and a documented pre-commitment will help clients preserve and grow their investments.

![Timing [time in] is everything Grant Alexander, Founder and Director, Private Client Holdings](https://bluechipdigital.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Grant-Alexander-150x150.jpg)