Global equity has been the best asset class for local investors over the past decade. What has been the main driver?

That’s right. Global equity returned 19% per year in rand terms over the past decade to end August (as measured by the MSCI All Country World index). Part of the story is rand weakness. The currency traded at R7 against the dollar 10 years ago. As it depreciated, it added about 9% per year to the return from global equity for local investors.

But the main reason has been that global equities performed well in dollar terms, despite the March 2020 crash. The return in the 10 years to the end of August was in the top 15th percentile of all 10-year periods since 1988.

But this headline performance hides quite a divergence, doesn’t it?

Indeed. We can slice and dice it in many ways, but let’s just look at it from a regional and a style basis.

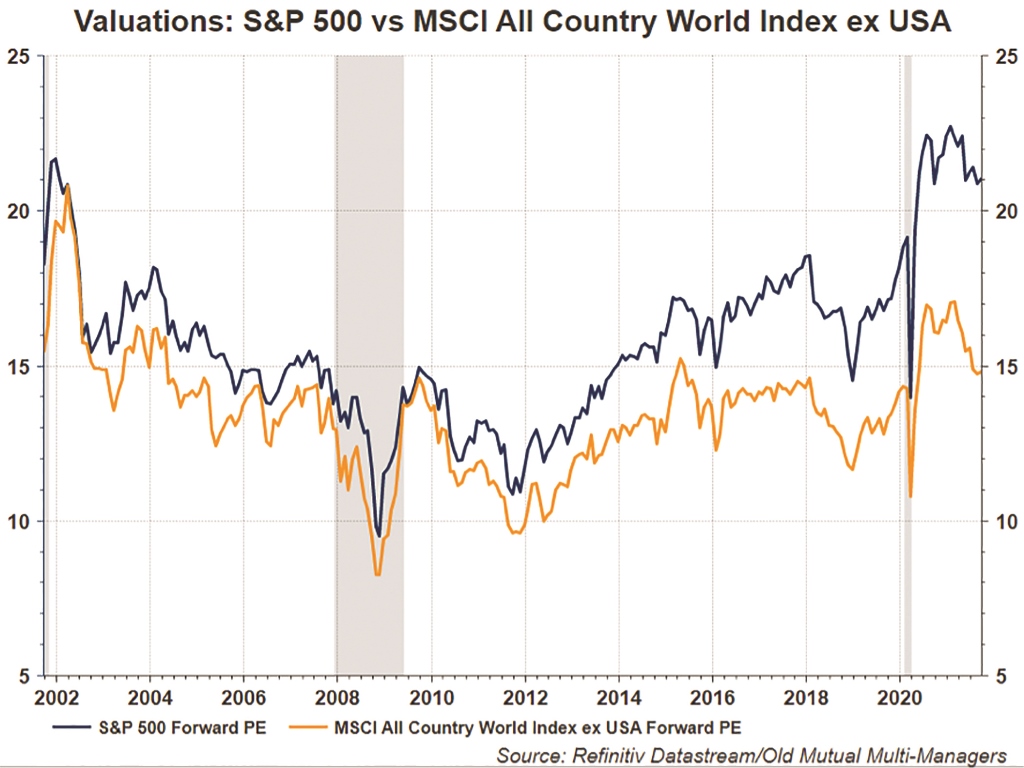

On a regional basis, the US has led the way over the past decade by some distance, while non-US equity returns were much more muted. The US is by far the biggest market in the world, accounting for more than half of the major global equity benchmarks, whether you use MSCI, FTSE or Datastream.

The US S&P 500 returned 16% annualised over the past decade, compared to 7% in dollars for non-US equities (the MSCI All Country World ex US index)

Now there are several reasons for the US outperformance, one of which is that the dollar strengthened over this period, which does depress the returns from outside the US somewhat. Another reason is that US economic growth far outperformed that of Europe and Japan over this period, while commodity producers and emerging markets disappointed relative to expectations.

But perhaps the biggest reason for the outperformance is simply the phenomenal performance of the big Internet platform companies, sometimes simply called the FAANGs (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google) or FAMANGs (adding Microsoft to the list). These companies have managed to capture increasing amounts of market share from their more established competitors over the last decade, using disruptive business models and technologies.

The same level of success was broadly absent in other parts of the developed world, driven by a combination of of less permissive regulation, less access to readily available private capital needed to support the growth of such disruptive models during their early stages, and less focus on delivering shareholder returns.

This brings us to the style discussion.

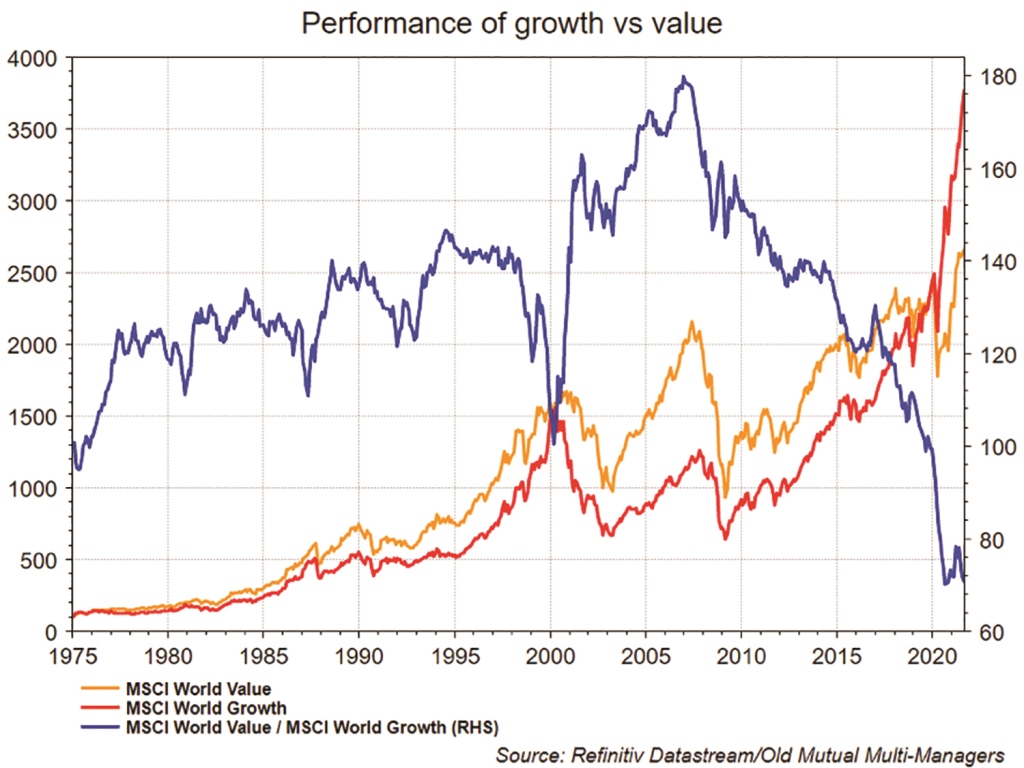

One of the most notable investment trends over the past decade has been the outperformance of “growth” as an investment style over “value”.

Broadly speaking, “growth” companies can generate their own earnings growth, often by taking market share and therefore are not as dependent on economic growth. The big Internet platform companies are classic examples of growth companies, as they have been able to deliver fantastic growth to investors over the last 10 years. Value companies are those unloved shares trading at cheap valuations but that typically need a strong economic cycle to boost profitability.

How should investors think about the impact of low interest rates on growth companies?

In theory, today’s share price reflects the present value of future cash flows a company is expected to generate. Those future cash flows are discounted back to the present using prevailing long-term real government bond yields, with lower rates making them more valuable today.

The key, however, is that growth companies benefit more from lower interest rates as they have a longer runway of expected cash flows when compared to value companies, who tend to enjoy expected cash flows much sooner. Some analysts even refer to growth companies as long duration assets, like long bonds.

This can potentially explain why US shares outperformed counterparts in Europe or Japan. However, low rates by themselves are not enough, as both Europe and Japan have lower prevailing interest rates – negative rates in fact. What also played in favour of US stocks was a continuous ability to deliver earnings growth and margin expansion in line or ahead of expectations, particularly among the tech innovators.

Do you think value can ever make a comeback?

Value companies outperformed their growth counterparts before the global financial crisis in 2008, supported by a booming global economy and a continued de-rating of growth stock valuations from the very elevated levels achieved at the height of the dot.com bubble in late 1990s. But the tepid economic growth environment after the 2008 crisis favoured growth companies, as investors were willing to pay up for scarce growth.

As a result, the valuation spreads between value and growth companies have once again reached close to extreme levels. Add to this a strong global economic recovery and better fundamentals and growth forecasts for value companies, and we could see market sentiment continuing to support value companies going forward. I think the question around the length of the current market sentiment is a valid one, but very difficult to predict.

Within this long outperformance of growth over value, however, there have been mini cycles. Even over the past year, there were periods when value outperformed, particularly after news of successful vaccine trials broke in November 2020.

Therefore, diversification across investment styles is important, particularly in the global equity universe, where these factors are much more prevalent than locally. This is because the breadth and depth of global equity markets allow managers to express their preference for a specific investment style without increasing the risk resulting from undesirable concentration levels in their portfolios. With the small number of companies listed on the JSE, this approach becomes more challenging.

What about quality as a style?

I should add that different investors will have slightly different ways of classifying companies, but broadly speaking, “quality” is an investment style where investors focus on companies with strong balance sheets and competitive advantages, such as having very well-known consumer brands.

These shares tend to be more defensive in nature, which means that they hold up better than the broader market during a selloff, which is what we experienced during the March 2020 market drawdown. In a market environment dominated by an uncertain future, investors tend to support the predictability and visibility of annuity-type earnings streams characteristic of quality companies. On the other hand, such companies tend to lag during subsequent market recoveries, as investors turn their focus to areas of the market that are likely to do well in an economic recovery.

How should a typical investor view all these various styles? Should you jump between them, or just pick one and stick to it?

I don’t think one can successfully time when a particular investment style will come into favour or fall out of favour, as these shifts in performance trends tend to only become apparent with the benefit of hindsight. Moreover, being caught on the wrong side of that trend could be detrimental to relative performance, given the length of such cycles. Therefore, our approach in the global equity fund is to combine fund managers whose investment philosophies and processes tend to be broadly underpinned by different investment styles.

…our approach in the global equity fund is to combine fund managers whose investment philosophies and processes tend to be broadly underpinned by different investment styles.

But I also don’t think that managers need to be purists and cling dogmatically to a specific investment style, as we acknowledge that markets dynamics can change over time, and we wouldn’t want them to miss out on any potential investment opportunities. So, in our research we look for managers who stick to their knitting and apply their process consistently over time rather than chase the latest market fads, but who can also be quite pragmatic in their investment approach.

Ultimately, we spend most of our time making sure our portfolios are properly diversified and balanced so that we are not dependent on the performance of any one style or market cycle.

South Africa is an emerging market. Should South African investors have a separate allocation to emerging market equities, or is that doubling up on risk?

I think a separate allocation is warranted and we have emerging market (EM) specialist managers in our global equity fund.

There are three reasons for this. South Africa is a small portion of the global emerging markets universe, accounting for 3% of MSCI’s emerging markets index (and less than 1% of the global index). There is a lot of opportunity out there in the emerging markets universe. It is also worth noting here that this universe comprises a heterogeneous selection of emerging markets, with each market offering investors a very different set of investment risks and opportunities.

Taking South African investments as proxy for emerging market exposure leaves local investors deprived of many potentially rewarding opportunities that tend to be unique to other emerging markets.

Secondly, that EM universe has changed dramatically over the past decade or so. It is now firmly centred on Asia, and with a much larger exposure to technology shares and the growing middle-class consumer in those countries. It is much less of a proxy for commodity prices, which is what South African equity is to an extent.

Thirdly, we have long believed that the global equity benchmarks have too little exposure to emerging markets, only 12% even though emerging markets account for a much larger share of global economic activity.

There is a concern that global markets look expensive. Is this a good time to invest offshore?

Overall valuations look stretched by historical standards, but again we need to scratch beneath the surface. For instance, the forward price: earnings ratio on the MSCI All Country World index is 18, which is near a level it last was in the early 2000 in the wake of the dot.com bust.

But we need to bear in mind that interest rates are much lower today than in 2000 and this eliminates the potential for either cash or bonds as a suitable investment alternative to equities. For instance, the 10-year US government bond yield is 1.3% versus 5% in 2000. European yields are negative. You can’t ignore that.

Valuations are very different across regions and companies. The US is most expensive because investors are prepared to pay up for those growth companies. Other markets are much cheaper.

Finally, global growth is positive, and companies are generating incredible earnings. In this macro environment, it makes sense to remain invested.

However, elevated valuations do suggest that the easy money has been made, and that investors should not necessarily expect the kind of returns we saw in the previous decade.

Speaking of managers, where do you stand on the active vs passive debate?

I think the main thing is that investors need to get value for money. If you can find active managers who outperform, it is worth paying somewhat higher fees. If you can’t, indexation is an attractive option.

We believe that skilled active managers earn their fees and then some. Investors just need to be patient. You won’t get positive alpha every day. It is lumpy.

We believe that skilled active managers earn their fees and then some. Investors just need to be patient. You won’t get positive alpha every day. It is lumpy.

How do you find these managers?

We start by doing a quantitative screen, using the global databases that we have access to. Here we look for some basic characteristics like track record, size, domicile, benchmark, etc. From this screen we can do more qualitative research on a short list of managers.

The final step is to spend time with managers to find out what makes them tick. We really want to understand their philosophy and process. We want to know who the key people are and how they interact. How do they generate ideas? How do these ideas end up in a portfolio? When do they buy and when do they sell? How is risk managed?

Once a manager is appointed, we have regular engagements with them to monitor performance, but mostly to make sure we still understand what is behind the performance and whether that remains consistent with their investment approach. Once we identify truly talented stock pickers, we tend to stay invested for the long term and in some cases we have been invested with the same global manager for over a decade.

The OMMM Global Equity fund was launched in March 2020 as a dollar-based UCITS fund. Despite the recent inception date, it is worth noting that our expertise in global manager research expands close to two decades.