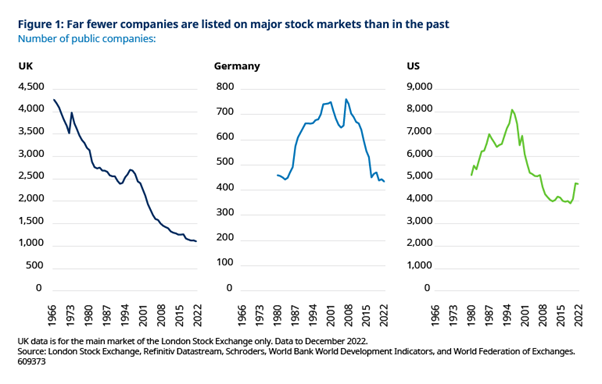

In 1996 there were over 2,700 companies on the main market of the London Stock Exchange. At the end of 2022 this had collapsed to 1,100 – a 60% reduction.

The figures look even worse when viewed over a longer time frame. There has been a near-75% fall in the number of UK-listed companies since the 1960s (see chart, below).

The stock market demise has been a global trend

Individual countries like to beat themselves up about their failings on this front but the reality is that it has been a global trend.

Europe’s downturn started later, but Germany has shed more than 40% of its public companies since 2007.

Even the US, often admired from afar, has experienced a 40% drop since 1996. This is even after allowing for the US boom in initial public offerings (IPOs) in 2021.

What’s happened?

Too few companies have wanted to join the stock market, and a steady stream have left, mainly after being bought.

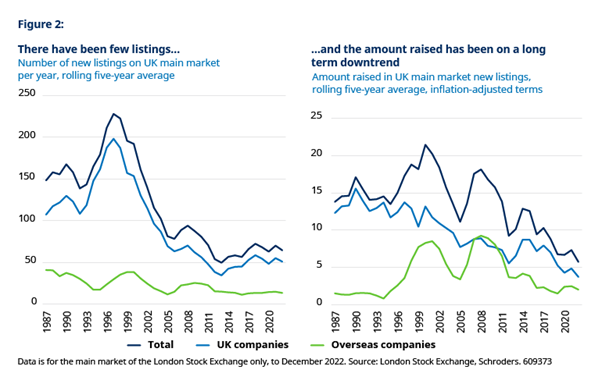

In the US, over 300 companies a year, on average, joined the stock market between 1980 and 1999. Since, there have been only 129 a year. In the UK, the number of new listings dropped after the financial crisis and has failed to pick up meaningfully since.

Money raised in UK IPOs has also been on a steady downtrend. For UK-based companies this trend set in in the early 1990s. For overseas companies, it has been in the past ten years.

Even those that have joined the stock market have waited longer before doing so. The average age of a US company on IPO increased from eight years in the two decades until 1999 to 11 years since.

Stock market investors fail to access a large segment of companies

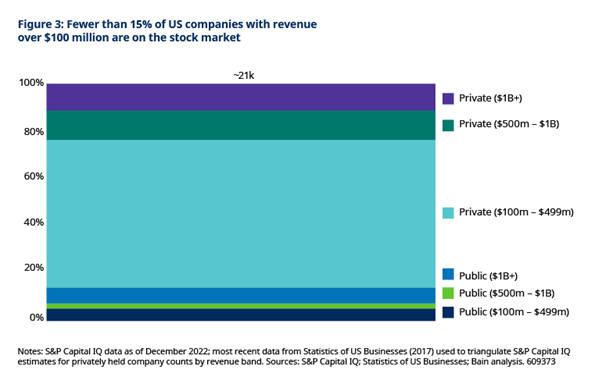

The net effect of all of this is that the stock market now provides exposure to a dwindling proportion of the corporate universe.

For example, fewer than 15% of US companies with revenue over $100 million are listed on the stock market. Ordinary savers are largely deprived of the opportunity to invest directly in the rest.

Why such change?

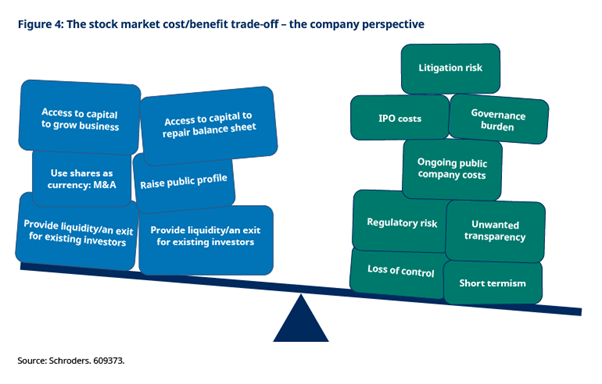

There are two main explanations. First, the cost and hassle of being a public company has increased.

Recent research has found that the average UK company’s annual report has increased in length by 46% in the past five years1. For FTSE 100 companies it now stands at 147,000 words and 237 pages.

This trend has been global and has also happened in the “lighter-touch” regulatory markets such as London’s Alternative Investment Market (AIM). The average number of words in an AIM company’s annual results is understandably much lower, at 46,000. But the rate of increase here has been even higher than among larger companies, up 51% in the past five years. Such “door-stopper” reports take time and money to produce.

Other issues counting against public markets in the cost-benefit trade-off include loss of control, unwanted transparency, perceptions around short-termism – and more (as below).

The other important reason why companies have turned their back on a stock market listing is that another source of financing has become more widely available. One that comes without many of these perceived drawbacks: private equity.

Private equity has grown from a $500-600 billion industry in the early 2000s2 to be worth more than $7.5 trillion in 20223. With this growth, the size of the cheques the industry can write has soared. It can now finance companies to a much later stage of their development than before.

When Google (now Alphabet) joined the stock market in 2004 it had only raised $25 million from private markets beforehand. Today’s biggest unicorns can raise tens of billions of dollars. Would stock market investors get the chance to invest in Google at such an early stage today? Unlikely.

Companies are not only attracted to private equity for the money. The best private equity investors also have deep sector expertise and take a much more hands-on approach to driving value. They are sought after by investors and companies alike.

This is a problem for private investors

The stock market is the cheapest and most accessible way that savers can participate in the growth of the corporate sector. Private equity has historically been the stomping ground of large institutional investors – not ordinary savers.

But, with companies choosing to stay private for longer, investors who focus solely on the stock market are missing out on an increasingly large part of the global economy. Many of these companies are in high-growth, disruptive industries. If high-quality companies find little reason to go public, the risk is that over time the quality of the public markets deteriorates. Should this occur, returns from public equity markets in aggregate could move structurally lower relative to private markets.

Where able, investors will need to broaden their scope and embrace private assets to avoid missing out. But to date, this isn’t something which has been easy for ordinary savers to do. It is they who stand to bear the brunt of these developments.

A regulatory hope

In the UK and Europe, regulators and providers have responded by establishing new investment vehicles known as the ELTIF (European Long-term Investment Fund) and for UK investors the LTAF (Long-term Asset Fund). Both aim to give individual savers access to a wider range of investments, including private markets.

While this should be welcomed, we should not lose sight of the other area where focus is needed: improving the appeal of a stock market listing relative to private ownership.

In the UK this has been long-recognised as an issue – as long ago as in 2012, the Kay Review highlighted the ways the UK equity market was failing to serve investors and companies – but it has recently been gathering a head of steam. We’ve had the Hill Review in 2021, the Edinburgh reforms in 2022, and a number of recent proposals for how to revitalise interest from pension funds and insurance companies in equity markets.

Sources:

¹The Quoted Companies Alliance: A never-ending story

²McKinsey & Co: A routinely exceptional year

³McKinsey & Co: Private markets turn down the volume

Important Information

For professional investors and advisers only. The material is not suitable for retail clients. We define “Professional Investors” as those who have the appropriate expertise and knowledge e.g. asset managers, distributors and financial intermediaries.

Any reference to sectors/countries/stocks/securities are for illustrative purposes only and not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument/securities or adopt any investment strategy.

Reliance should not be placed on any views or information in the material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.